There is a lot of talk in the small, curious world of theoretical physicists, and in the swarm of admiring hand-wavers, paper-skimmers, and buzzword-retailers that surrounds them, myself included, about the arrow of time. This arrow, which is no doubt fletched with the remnants of scores of papers debating its existence, speeds in only one direction. Nobody knows why. “The equations of physics,” so the story goes — I don’t know these equations, but I have this on good authority — can “run in either direction”. Why, then, do they run forward from now until tomorrow, rather than backward from tomorrow until now? Nobody knows, and it seems there is only a very mumbling and ill-equipped dude by the name of Entropy keeping tomorrow from crashing into yesterday and causing a mass of utter confusion.

One day, I will write down a theory about all this, and convince my physicist acquaintances to read it, perhaps along with some bitters for stomach calming or, perhaps more likely, a tube of caviar paste which they are, strangely, quite fond of. Today is not that day.

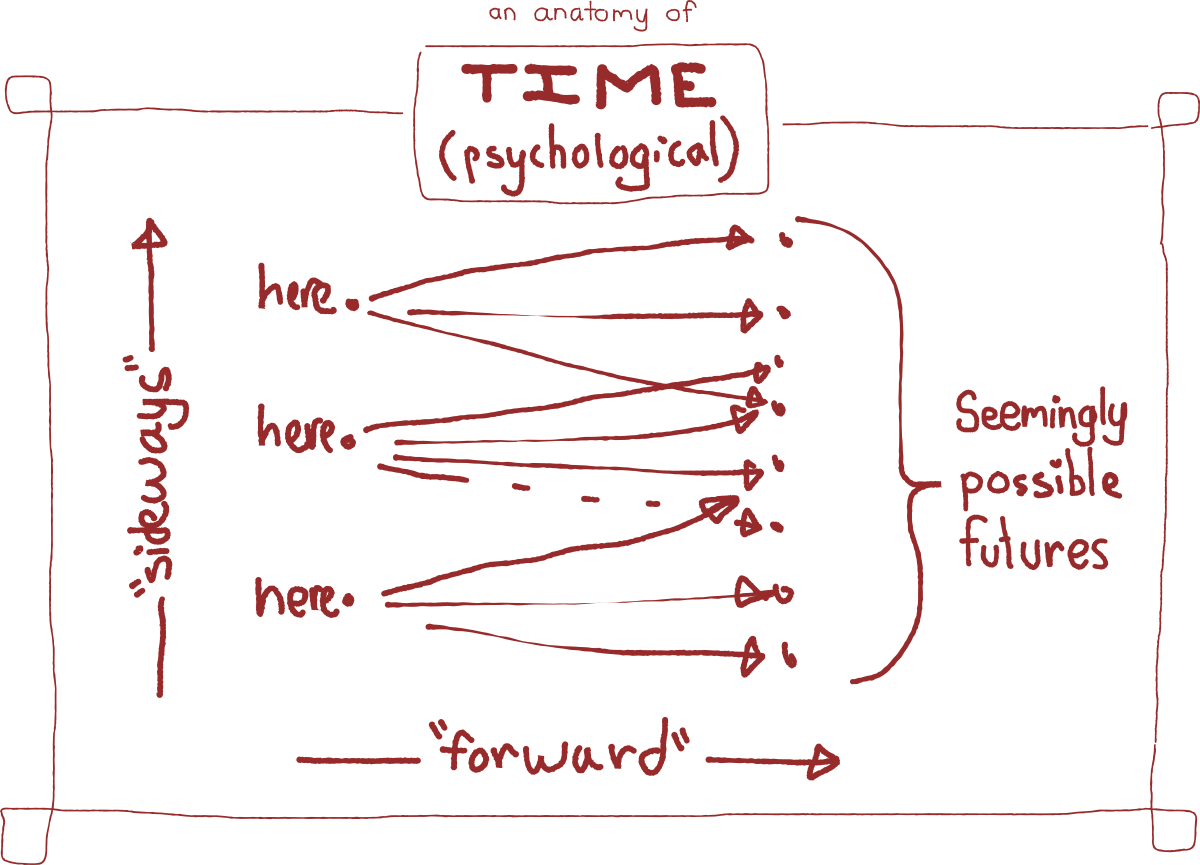

Today the arrow of time I want to discuss is psychological, not physical, and it moves — if it can be said to move at all — not necessarily forward or backward, but primarily sideways.

What could this possibly mean?

Time, psychologically, has at least two dimensions. There is the forward and backward dimension of the past we remember and the future we imagine; and there is an up, down, or sideways dimension of our current mental state and outlook. Why is our mental outlook a dimension of time? Because as it changes, the futures we can imagine also change. It is as though we are traveling sideways in a 2-dimensional plane of time: the forward-looking line of plausible futures changes with each version of now we inhabit. As usual, a scientific plot will help:

This is of course not the whole story. We behave as though there’s a future out there, and we’re going from here to there, but in fact there isn’t a there at all, only a interminable here that changes as it goes along, such that one here is vaguely related to what we did in the previous one. Brilliant, eh? No. It’s the biggest cliché since Zen and the Art of Whatever-You-Jolly-Well-Please. It’s also true.

The idea of a here, and a there, and some kind of passage in between is an important illusion. It’s important because without an imaginary future over there that we can be illogically striving towards, here tends to get increasingly shabby. Entropy, remember? He was talking about people, not futures, but Victor Frankl said it very well.

If there is what we imagine could be, should be, or must be — say, a world in which humans are living in something like harmony with the Earth, or a version of myself that has moved beyond Earth-destroying economic entanglements — here is our starting point, the situation as it is: a world getting closer to ecological collapse each day, and myself still eating, directly or otherwise, from the economic systems that are abusing the planet.

Futures have a function, and that is to alter what we do in the present. To serve this function, though, they have to be believable. To be believable, we have to be able to see a way to get between here and there. To see a way between here and there, through or around the obstacles that lie in between, we have to be looking from the right spot. To get to the right spot, we have to be able to move, not just forward in time, but up, down, and sideways, such that we can change our outlook until we catch sight of a future that looks so frickin’ fantastic that we’ll get — no, we’ll jump — up off our sorry butts and start trying to drag ourselves, possibly our friends and relatives or anyone else who will listen, possibly even the whole world, in that direction.

In extreme cases that are successful, this is called being a visionary. In extreme cases that are unsuccessful, it’s called being insane. Otherwise, it’s called the human condition. How I feel, what I ate for breakfast, what calamitous or inspiring thing I’ve just been informed of all change my outlook, and therefor what seems to lie between here and there. My movement up, down, and sideways in time is determined by a host of factors, only some of which are under my control. The more I understand them and learn to navigate, the better my view can be.

All this talk of viewpoint could be dismissed as romantic delusion, but the fact is that where we are — what forward-looking line we can see — is critical for practical, real-world effectiveness.

Famous change agents are famous in part because they were unusually capable navigators of perpendicular time, and were able to see a route between here and there that was invisible to others: Ghandi, for example, a route of non-violent resistance from tyranny to self-rule; MLK a route of non-violent resistance from oppression to civil rights; Victor Frankl a route from despair to meaning, no matter the circumstances; Elon Musk a route through a $100,000 battery-powered roadster from fossil-fueled disaster to universal clean energy; Donal– …. no, never mind. There are negative visionaries as well: those who are able to see a route from here to a version of there that is generally repugnant enough from where many people sit that they can’t see the line of possibility and are therefor taken horribly by surprise. Visionaries are nearly always underestimated, since their futures are simply impossible when viewed from where most people are looking from.

Every visionary is some percentage a failure. The vision of what could be — peace between Muslims and Hindus in India for example, or justice and equality between races in the USA — rarely fully comes true. Reality falls short of the mark, but it can get much closer thanks to someone finding a place to stand where they could catch a glimpse through a pin-hole of possibility, and then describe it convincingly enough to bring others close to the same viewing point.

Views of what’s possible create their own probabilities. The question is not which view of what’s possible is “most true”; the question is: which view of what’s possible will lead to the best result?

I think the heart, that organ of surpassing sagacity and sometimes of extreme foolishness, generally knows this. It is more prudent than the mind, and invests only in what is inspiring, knowing that what is inspiring has the best chance of success.

As an activist in any arena, even the petri dish of my own consciousness, I have to keep in mind that navigation of mindset and motion on the ground are of equal importance. Just getting to the visionary place where I can see a way forward does nothing; pushing for change without getting to that place may do less than nothing, because the pushing might not be pointed in the right direction.

We need to have an inspiring vision, whether it’s of a more beautiful world, or a more enlightened version of myself, and we need to know in our hearts that this vision is possible. At the same time, we need to look very close to home, in both time and space, for the real action that will move us forward towards whatever a positive future will look like, whether it matches the vision or not. Like belief, a vision of the future is a tool that can be used for adjusting the knobs and dials of our own minds and motivations. Meanwhile, the knobs and dials of my mind affect the future I can see, and so believe.

Between here and there is an imaginary landscape. It is by changing the version of here I’m inhabiting that I can get the virtual reality out there to leverage the evolution of here so that, in time, there can become real.